world news

THE SECRETARY-GENERAL — REMARKS AT 2024 ECOSOC FORUM ON FINANCING FOR DEVELOPMENT FOLLOW-UP

Published

2 years agoon

By

Shanieka

New York, 22 April 2024

Excellencies, ladies and gentlemen,

I thank ECOSOC for convening this forum on a topic that is essential to development and the better world we all seek — financing.

Financing is the fuel of development.

Yet many developing countries are running on empty.

This is creating a sustainable development crisis.

A crisis of lingering poverty and rising inequality.

A crisis of hunger, lack of education and shattered infrastructure.

A crisis of climate catastrophe and shocks that are becoming more frequent and acute.

And a crisis that, if left unchecked, will undermine stability, prosperity and peace for decades to come.

Crisis after crisis, challenge after challenge, all tied together by a common thread.

Lack of financing.

Many developing countries are simply unable to make the investments they need in sustainable development, and the systems and services their people require.

And when they turn to the global financial system for help, they find that it is unable to provide a global safety net to shield them from shocks.

They find a system incapable of helping them forge stability or sustainability.

They find a system that they had no hand in creating, no voice in shaping — and that remains unresponsive to their needs.

My friends, they find a system that is broken.

The result is plain to see.

The Sustainable Development Goals are hanging by a thread — and with them, the hopes and dreams of billions of people around the world.

The world faces an annual financing gap of around $4 trillion to reach the SDGs — a sharp rise from the $2.5-trillion gap one year before the COVID-19 pandemic.

This growing financing gap is matched by a growing financing divide — between those countries that can access financing at affordable rates, and those that cannot.

This is no longer a question of “haves” and “have nots.”

This is a question of who has access to finance when they need it — and who does not.

This is a question of justice.

Look at the global financial system’s handling of debt.

Many developing countries are being crushed under a steamroller of debt.

Four out of every 10 people worldwide live in countries where governments spend more on interest payments than on education or health.

Annual debt service payments in the world’s poorest countries are 50 per cent higher than they were just three years ago.

In sub-Saharan Africa, debt-servicing consumed nearly half of all government revenue in 2023.

In country after country, development gains are quickly erased by relentless crises, with debt service payments impeding critical social spending and investments in the SDGs.

Money is flowing in the wrong direction — from the countries who need it to the countries who don’t.

When it comes to debt, developing countries are climbing a ladder planted in quicksand.

Excellencies,

A growing economy is the best way to reduce debt burdens and raise domestic revenue for key investments.

We need a surge of investment to bridge the financing gap and give developing countries a fighting chance to build better lives for their people.

We must continue pushing for an SDG Stimulus of $500 billion annually in affordable long-term finance for developing countries.

The Stimulus was welcomed by world leaders at the SDG Summit and in the G20 New Delhi Leaders’ Declaration.

Now it’s time to move from words to action and deliver affordable, long-term financing at scale.

First — developed countries need to step-up, led by the G20.

Discussions on general capital increases for Multilateral Development Banks should start now.

Meanwhile, donors must meet their official development assistance commitments.

In 2022, only four countries met or exceeded the agreed target of 0.7% of Gross National Income.

Official development assistance has risen on paper, but it is increasingly spent within donor countries, leaving developing countries without the resources they need.

I call on all donor countries to meet their targets, and get this financing flowing.

Second — we need Multilateral Development Banks to make better use of the resources they can already access, at no additional cost to shareholders.

This includes finding ways for MDBs, central banks and credit rating agencies to greenlight ways to stretch Banks’ balance sheets, leveraging the vast sums of callable capital that the shareholder countries of MDBs have at the ready, sitting in central banks.

It means deploying innovative financing systems — for example, hybrid capital bonds that increase lending capacity and attract private capital.

And MDBs must readjust their business models to better leverage private finance at a reasonable cost for developing countries.

Third — we need bold action to ease the debt distress.

Any new financing should be used for productive investments and sustainable development — not to service unsustainable and unaffordable debt.

And the debt-restructuring systems and mechanisms in place need to be strengthened.

The Debt Service Suspension Initiative and the G20 Common Framework for Debt Treatments have not delivered on their promise.

The Debt Service Suspension Initiative was too limited in scope and duration, expiring just as interest rates skyrocketed.

Debt repayment pauses must be considered for countries facing liquidity crises.

And for those countries bearing the weight of unsustainable debt, it’s time to revamp the debt resolution architecture to provide deep relief that avoids repeat crises.

Regardless of intent and efforts, the Common Framework has failed to provide this.

Nor has it served many of the countries that face the greatest unresolved debt problems.

It’s time for change.

And fourth — we need to increase developing countries’ representation across the system and every decision that is made.

This July is the 80th anniversary of the Bretton Woods Conference, which ushered in today’s international financial architecture.

But the countries who need these systems and institutions most were not present at their creation — a lack of representation that continues to this day.

In the name of justice, they need and deserve a seat at the table.

The Summit of the Future in September and next year’s Financing for Development Conference will be key opportunities to gather the world together to reform the global financial architecture so it serves all countries who need it.

Excellencies,

Let’s make the most of these opportunities.

Now is the time for ambition.

Now is the time for reform.

Now is the time to shape a global economic and financial system that delivers for people and planet.

I look forward to standing with you in this great effort, as we shape a more inclusive, just, peaceful, resilient, and sustainable world for present and future generations.

Thank you.

You may like

-

Over 5.7 Million Haitians Face Hunger as UN Hot Meals Program Reaches Just a Fraction of Those in Need

-

UN Youth Advisory Group to Launch Health and Food Security Podcast Series

-

UN Secretary-General appoints Carlos G. Ruiz Massieu of Mexico as the Special Representative of the Secretary-General for Haiti and Head of the United Nations Integrated Office in Haiti

-

UN Marks 20th Anniversary of Responsibility to Protect Amid Global Turbulence

-

Every year on May 29th, the United Nations marks the International Day of UN Peacekeepers

-

Women-Led Organizations in Crisis: UN Warns of Widespread Shutdowns Amid Funding Cuts

world news

Haiti Begins Preparing Polling Stations as Long-Delayed Elections Finally Take Shape

Published

1 month agoon

December 4, 2025

Haiti, December 4, 2025 – For the first time in nearly a decade, Haiti is taking concrete steps toward holding national elections — and the most visible sign came this week with confirmation that more than 1,300 polling centers are being readied across nine departments. After years of political paralysis and escalating gang rule, the preparation of voting sites is the clearest signal yet that Haiti may finally be inching back toward democratic governance.

According to Haitian electoral authorities, 1,309 voting centers have been identified and are now being assessed for accessibility, staffing, and security. These centers form the backbone of a new electoral plan that has been quietly but steadily advancing since early November, when officials submitted a draft elections calendar. That calendar marks August 30, 2026 as the date for Haiti’s first-round general elections — the first since 2016. A second round is tentatively set for December 6, 2026, with a new president expected to be sworn in on February 7, 2027, restoring the constitutional timeline that Haiti has missed for years.

and security. These centers form the backbone of a new electoral plan that has been quietly but steadily advancing since early November, when officials submitted a draft elections calendar. That calendar marks August 30, 2026 as the date for Haiti’s first-round general elections — the first since 2016. A second round is tentatively set for December 6, 2026, with a new president expected to be sworn in on February 7, 2027, restoring the constitutional timeline that Haiti has missed for years.

The progress accelerated on December 2, 2025, when Haiti’s transitional presidential council formally adopted a new electoral law — a prerequisite for launching the process. International partners, including CARICOM, the United States, Canada, and the United Nations, have long pressed Haiti to move toward elections, but repeated security collapses made even basic preparations impossible.

The challenge now is enormous. The United Nations estimates that gangs currently control around 90 percent of Port-au-Prince, and violence continues in key areas targeted for polling. Attacks in regions like Artibonite — where voting centers are being prepared — highlight the fragile reality on the ground. Yet Haitian officials insist that stabilisation efforts led by the transitional government and international support missions will allow the election machinery to keep moving.

Still, the symbolism of seeing polling centers mapped, listed, and prepared cannot be overstated. For a population that has lived through presidential assassinations, mass displacement, gang takeovers, and repeated postponements, the simple act of preparing schools and buildings for voting feels like a long-overdue return to civic possibility.

Haiti is nowhere near ready to vote today — but for the first time in years, the infrastructure of democracy is being rebuilt, room by room, center by center.

Angle by Deandrea Hamilton. Built with ChatGPT (AI). Magnetic Media — CAPTURING LIFE.

USA

UN Welcomes Trump-Brokered DRC–Rwanda Deal, But Keeps Its Distance

Published

1 month agoon

December 2, 2025

December 2, 2025 – The United Nations is cautiously welcoming a new peace agreement between the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) and Rwanda, signed in Washington today under the heavy branding of President Donald Trump – but it pointedly notes that the UN was not directly involved in the talks.

At the UN’s regular press briefing, the spokesperson was pressed on whether the White House had cut New York out of a process where the UN has had “a longstanding role on the ground.”

“This is not an agreement that we are directly involved in,” the spokesperson said, adding that UN colleagues in the region had been “in contact with the US,” and that the organisation welcomes “this positive development towards peace and stability in the Great Lakes.”

The UN went out of its way to stress complementarity, highlighting the African Union’s mediation role, the involvement of Togo’s President Faure Gnassingbé and Qatar, and the continuing work of UN peacekeepers and political missions in support of both the new Washington process and the earlier Doha track. What matters, the spokesperson said, is not “the configuration,” but whether there is “actually peace on the ground.”

In Washington, the optics told a different story: President Trump flanked by Rwanda’s Paul Kagame and the DRC’s Félix Tshisekedi at the newly rebranded Donald J. Trump Institute for Peace, celebrating the so-called Washington Accords for Peace and Prosperity as a “historic” breakthrough that ends decades of bloodshed in eastern Congo.

According to U.S. and international reporting, the accord commits Rwanda to withdraw its forces and halt support for the M23 rebel group, while Kinshasa pledges to neutralise the FDLR and other militias operating near the Rwandan border. The agreement also folds in earlier frameworks signed in June, and is paired with bilateral economic deals giving the United States preferred access to critical minerals – cobalt, tantalum, lithium and other resources that have long fuelled conflict in the region.

Trump and his allies are framing the deal as proof he can deliver in months what multilateral diplomacy has struggled with for decades. A recent White House article touting his Ukraine summit casts the DRC–Rwanda track as part of a broader record of “cleaning up” global wars and restoring “peace through strength.”

But even as the leaders signed in Washington, fighting between Congolese forces and M23 rebels continued around key eastern cities, and rights advocates warned that economic interests risk overshadowing justice and accountability for atrocities informed a report from Reuters and the Associated Press (AP).

That tension – between Trump’s highly personalised, bilateral style and the slower, rules-based multilateralism of the UN – was on display in the briefing room. Journalists pushed the UN to say whether it should have been more closely consulted. The spokesperson refused to bite, repeating that every peace effort has its own shape, and suggesting the UN will judge the Washington Accords not by the ceremony, but by whether guns go quiet in North Kivu and Ituri.

For now, the UN is standing slightly to the side of the cameras, signalling that it won’t compete with Washington’s moment – but it also won’t take ownership of a deal it didn’t design.

Angle by Deandrea Hamilton. Built with ChatGPT (AI). Magnetic Media — CAPTURING LIFE.

world news

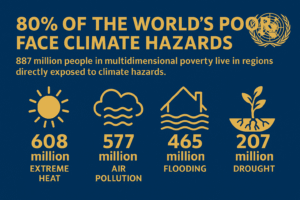

80% of the World’s Poor Face Climate Hazards — UNDP Sounds Alarm

Published

3 months agoon

October 24, 2025

By Deandrea Hamilton | Magnetic Media — CAPTURING LIFE

NEW YORK (October 17, 2025) — A new United Nations report has confirmed what many developing nations already know: climate change is punishing the poor first and hardest. Nearly 80 percent of the world’s 1.1 billion people living in multidimensional poverty — about 887 million individuals — live in regions directly exposed to extreme heat, flooding, drought, or air pollution.

The 2025 Global Multidimensional Poverty Index (MPI), released jointly by the UN Development Programme (UNDP) and the Oxford Poverty and Human Development Initiative (OPHI), calls the findings “a wake-up call before COP30.” It’s the first time global poverty and climate-hazard data have been overlaid, revealing how environmental stress and social deprivation now reinforce one another.

A World Under Double Strain

The report, titled Overlapping Hardships: Poverty and Climate Hazards, finds that among the world’s poorest, 651 million people face two or more climate hazards simultaneously, and 309 million confront three or four at once. The most widespread threats are extreme heat (affecting 608 million) and air pollution (577 million). Flood-prone areas house 465 million poor people, while 207 million live in drought-affected zones.

“These individuals live under a triple or quadruple burden,” said UNDP’s Acting Administrator Haoliang Xu. “To fight global poverty, we must confront the climate risks endangering nearly 900 million people.”

The Geography of Risk

The pressure points are clear. South Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa are the world’s epicentres of climate-linked poverty, hosting 380 million and 344 million vulnerable people respectively. In South Asia, a staggering 99 percent of the poor are exposed to one or more climate shocks, with 92 percent facing two or more.

million and 344 million vulnerable people respectively. In South Asia, a staggering 99 percent of the poor are exposed to one or more climate shocks, with 92 percent facing two or more.

The Caribbean and small-island developing states weren’t individually ranked but are highlighted as especially exposed — combining low-lying geographies, fragile ecosystems, and high dependence on tourism. Analysts say the MPI’s message is unmistakable: without climate-resilient development, hard-won progress could unravel overnight.

The Rich-Poor Divide Deepens

Lower-middle-income nations shoulder the greatest burden, with 548 million poor people exposed to at least one hazard and 470 million to two or more. “Countries with the highest levels of poverty today are projected to face the steepest temperature increases by the end of the century,” said Pedro Conceição, Director of UNDP’s Human Development Report Office.

That projection underscores why the Caribbean, Africa, and parts of Asia argue that wealthy nations must help fund climate adaptation, debt relief, and just-transition mechanisms.

From Recognition to Action

The UNDP urges world leaders gathering next month for COP30 in Brazil to align climate commitments with poverty reduction strategies — strengthening local adaptation, scaling climate finance, and embedding environmental resilience into every development plan.

“The crisis is shared, but the capacity to respond isn’t,” the report concludes. “Without redistribution, cooperation, and climate-resilient policy, the world’s poorest will remain trapped between heatwaves and hunger.”

Why It Matters for the Caribbean

For island nations like The Bahamas, Barbados, and Turks & Caicos, the MPI’s findings hit home. Even where income levels are higher, inequality and geographic exposure magnify the risk: a single hurricane season can wipe out years of economic gains. The message to regional policymakers is clear — social protection, infrastructure, and environmental defence are no longer separate issues; they’re survival strategies.

As the world counts down to COP30, the UNDP’s data doesn’t just measure poverty — it maps who the planet is failing first.