What’s on my mind is a Turks and Caicos that deserves to be celebrated, not reshaped into something unrecognizable.

Yes, Providenciales has grown. It has welcomed businesses, ideas, and people from all over the world, and in many ways it reflects the beauty of a melting pot. But growth should not mean erasure. Progress should not require us to trade away the very soul of who we are.

There is a moment we are standing in right now that calls for intention. Stop. Pause. Preserve. Think ahead for the generations to come. All is not lost, but it can be, if we do not choose wisely.

Each Islander is unique to the island they are from. Even our dialogue carries the imprint of where we come from. Our accents, expressions, rhythms, and ways of telling stories quietly reveal our home islands. That is our power. That is our beauty. The true richness of Turks and Caicos lives in its people as much as in its landscapes. Exploring and preserving our islands must also mean exploring and preserving their inhabitants, their knowledge, their traditions, and their ways of life. We are not here to invent something foreign. We are here to shape and mold what we have already been given. God has already provided the blueprint. We only need to slow down long enough to see what is right in front of us.

No one knows your country or your product better than you who have lived it. Why try to be something we are not? Each time we attempt to imitate another place, we lose a piece of our own lifestyle. A lived experience is what gives us the authority to shape our present and our future.

I envision the marketing and development of our family islands not as replicas of somewhere else, but as island treasures. Places where businesses rise from culturally focused initiatives, designed first with residents in mind, and where visitors are welcomed into an authentic haven that reflects what Turks and Caicos truly represents.

North Caicos as a living sanctuary. Lush, green, and respected. A place for nature trails, wildlife exploration, farming traditions, and environmental exhibitions, where development works with the land, not against it.

Middle Caicos safeguarded for its history and natural wonders. Its caves protected not only as attractions, but as classrooms. Its flamingos preserved as symbols of the fragile beauty we are responsible for protecting.

South Caicos honored as the salt and fishing capital. The rhythm of boats, salt ponds, and sea life forming the heart of its identity. A working island where maritime culture and sustainable fishing are supported, celebrated, and passed down.

Grand Turk restored and respected as a cultural and historical anchor. Front Street with its light and British flare revived with intention. The return of a strong public library and cultural spaces for those who adore history, storytelling, and research.

Salt Cay protected in its quiet uniqueness. A picturesque island lifestyle centered on stillness, craftsmanship, heritage, and community.

The heart of this vision is not tourism alone. It is our people.

Celebrate our island cultures. Create small businesses that allow islanders to thrive with dignity, love, and respect. Build economies that sustain us without displacing us. Let development work in service of community, not the other way around.

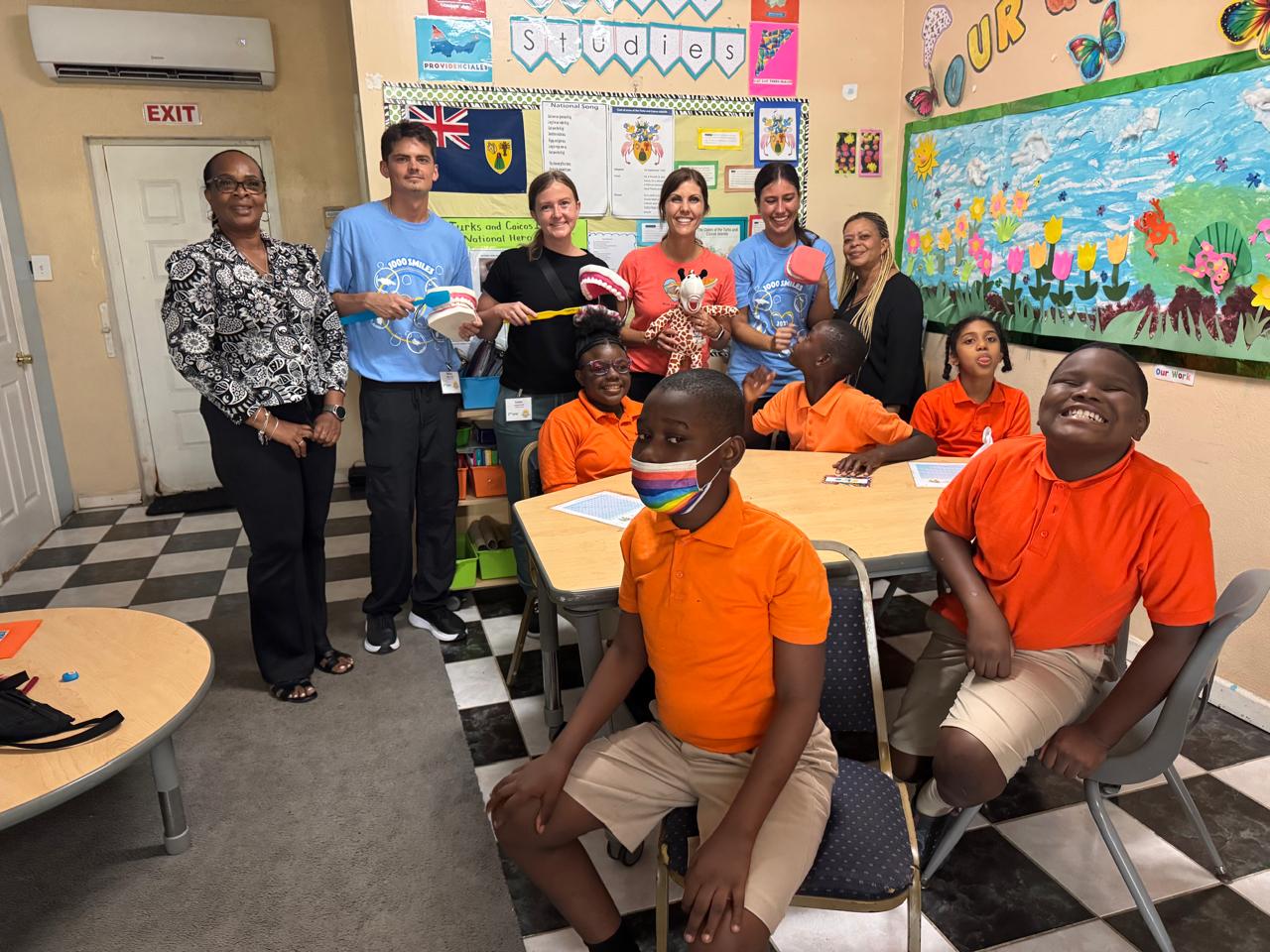

Teach our youth the trades, the arts, the skills, and the stories while our elders are still here to pass them on. Boat building, straw work, farming, fishing, cooking, music, storytelling, herbal knowledge, construction, and design. These are not relics. They are foundations.

From this, innovation is born. When young people are rooted, they can modernize tradition without losing it. They can bridge yesterday and today. They can create futures that honor the past instead of replacing it.

We do not need to become a concrete jungle to be successful. We do not need to mirror other places to be worthy. We do not need to sacrifice our identity to attract the world.

What we need is the courage to protect what is left, the wisdom to shape what is coming, and the commitment to ensure that being a Turks and Caicos Islander is not just a title, but a living experience our people can still feel, recognize, and pass on.

From Alicia Swann

Turks and Caicos Islander